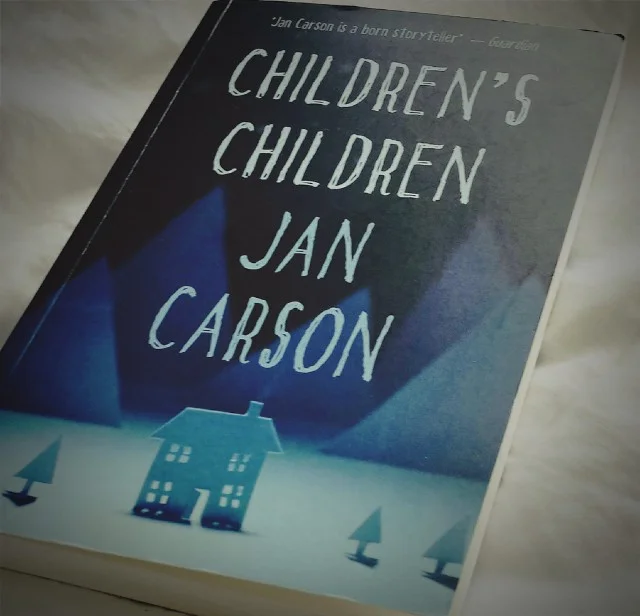

This was my travelling companion through the recent trips to Scotland and London. What a treat – these stories brimmed with a delightful cock-eyed surrealism and yet were also rooted in gritty reality, many of them set in east Belfast, with some really stunning turns of phrase here and there: ‘She worries constantly. The feel of it is a pain in her ribcage, as if worry is made of sand and the sand has gathered inside her and cannot be shifted while lying down’. And there was lots of humour, but the overwhelming mood was pretty dark, which really appealed to me. On many occasions I was reminded of the engaging, off-kilter world of Paul Durcan’s poetry. The characters - and their situations - really stayed with me, always a good sign.

Scotland March 22-24: bonnier than ever

Driving north east into the brightness after coming off the ferry, there’s a sense of déjà vu – I’ve done this journey a few times for sure, but never with this excited sense of purpose - and I realise, never alone. I’ve always been with the family, or years ago in a van with Trevor Dixon and the country band, or a couple of years ago, with Ben Glover.

Picture by Jonathan Cosens, Moffat

And it feels good - middle of the afternoon, on the road with three shows to look forward to, arrangements all made for accommodation, tank full of petrol, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young on the stereo.

The towns in the west look familiar – beautiful little sandstone houses with views out over the Irish Sea, until the road turns inland and it’s rolling hills and bridges until we hit the motorway. And then it’s that motorway thing – miles and miles of two lane, overpasses and bridges and trucks.

The road pumps you into the heart of Glasgow before you really know it, and you find yourself on this elevated motorway that appears to run between the rooftops of the city, while you wait for your exit. And then it’s down to street level, where it gets complicated, a maze of one-way streets that suddenly open out into bypasses – the satellite navigation on my phone is a little slow on the uptake, so it tells you to turn left into streets that you’ve already overshot. I miss my turn into the hotel, and end up having to go five blocks north, eventually missing a turn and ending up back onto the motorway. Eventually I pull in beside the hotel, where construction workers are tearing up the street, and find my location, the engine roasted from the non-stop drive from the ferry.

The hotel is close to the top end of Sauchiehall Street, and I walk the whole way down to the Buchanan Galleries, just to stretch my legs after the journey and get a feel for the city. It convinces me that I should walk to the gig – it’s only a few blocks. So later I pack my rucksack with cables and CDs, and set out on foot with my guitar. I’m abruptly reminded of how steep some of the hills are in Glasgow. It’s a uniquely characterful city – a real sense of grit but a very elegant place, lots of beautiful stonework and tall windows and wide streets. I hear ‘Saturday Night’ by The Blue Nile in my head the whole time I’m walking – ‘when it’s cold and it’s starlight, and the streets are so big and wide’.

Live at The Admiral - picture by John Melrose

The gig is a treat – a lovely, low ceilinged basement room at the Admiral Bar, where I’m the guest of the Star Folk Club and The Fallen Angels music club. There’s a lovely support spot from Glasgow songwriter John McMeekin, and an audience who want to listen and engage. Afterwards, there’s a couple of pints a few streets away in the Horseshoe Bar. And then I walk back up Sauchiehall Street at midnight, with my guitar and my rucksack, feeling like a real musician.

Over breakfast the next morning, I rise and pack, check out of the hotel and take my stuff over to the car. And then I go for a walk in search of breakfast, and I sit in the window of a Pret A Manger and finish what I’ve been reading: Bukowski on Writing.

The book started unpromisingly with lots of whining letters to publishers and bitching about rejections, and then settled into something kind of wonderful. The main thing, surprise surprise, is to keep working, to stay honest, not to get greedy, not to get hooked on any kind of fame nonsense, and to stay alive to everything.

‘The secret is in the line,’ he says. ‘And I mean one line at a time. Lines containing factories, and a shoe on its side next to a beercan in a hotel room. Everything is here, it flashes back and forth. They are not going to beat us, not even the graves. The joke is ours; we pass through in high style; there’s nothing they can do with us’.

Closing the book, it’s back up the street, back in the car and on the road south, towards the Borders, where I have a house concert in Moffat. The scenery once I leave the city is kind of breath-taking – huge, rolling fields in shades of brass and gold, the motorway rolling down into the valleys in deep, slow curves, up again through dazzling little showers, the sun moving across the landscape, clusters of pines in the gaps between the hills. I have a sudden desire to pull into a layby and set off across the moor… But I’m hemmed in by heavy lorries and I press on into the early afternoon.

Live at Moffat - picture by Jonathan Cosens

Eventually – and much earlier than expected – I see a turn-off for Moffat, and as I approach the village there’s a car park on the left, with a sign that says ‘River Walks’. I pull in and park. On the ‘main road’ in front of me, a mallard duck flaps down into the centre of the road, shakes his tailfeathers, settles his wings and walks up the centre line, like he’s the mayor. I pull on my walking shoes and head up the river.

The water runs in a straight line through a shallow channel, over pebbles and roots – it’s a very musical accompaniment. Eventually there’s a gate and a path to my right that leads across open country and the main road beyond, back into the village. I take it, and find myself walking through the outskirts – glorious old sandstone houses with white window frames, dormer windows and slate roofs, ivy growing up the front, wrought iron gates and the rest. Absolutely beautiful old properties.

John Weatherby and his partner Mairi make me very welcome, giving over their spare room and welcoming a dozen or so friends into their ‘performance space’. There’s dinner and red wine and some songs and stories. And then more red wine. And eventually, when everyone has gone, John offers me a short single malt tour of Scotland, stopping off at Scapa, Old Pulteney and Highland Park before I navigate unsteadily to bed, my head buzzing.

The next day, the road north east is equally beautiful – more rolling hills and golden fields, and Kirkcaldy is gleaming with bright cold, and I park up and walk down the waterfront and up into the town centre.

Mary and Davey Stewart’s house is a beautiful space - I stayed here with Ben a couple of years ago and I remember it fondly. Nice old furniture, walls painted white and adorned with beautiful original art, the stairs edged by tasteful pieces of wood sculpture or pottery. And once again, I’m in the hands of gracious hosts.

Barbara Dickson joins me for a song at Kirkcaldy Acoustic Music Club

Kirkcaldy Acoustic Music Club is hosted by the Polish Servicemen’s Club in the town, and it’s just like I remember it being on my last trip, filled with warmth and welcome. From the minute I start, the stories and the songs just seem to connect. High point was when Barbara Dickson - who was in the audience, as an old friend of my hosts - accepted an invitation to come up for a song, and we sang a duet on the old Everly Brothers’ song ‘Sleepless Nights’, much to the delight of the audience.

(It was an evening of connection, and there’s no explaining it when it happens. It feels like it all just… rolls forward in solid forward motion. You could do exactly the same thing the next night and it could just as easily fall and lie flat on its back… But all three nights were filled with that sweetness of connection – when the ball hits the centre of the racket)

Thanks to my hosts, there are a few more single malts before bedtime, and the next day, heavy headed and dry-mouthed, I rise to a house brimming with brightness. It’s a wonderful day for heading west to the Irish Sea and home for Easter. I pack the car and make my way across the Forth, up through the midlands and west, the sky brightening at one minute and closing in the next, and showers blessing the landscape along the way.

Shelf Life: Carol Shields - The Stone Diaries

‘Not people die, but worlds die in them’

Yevgeny Yevtushenko

I’m not sure what made me pick up a copy of The Stone Diaries in a second hand bookshop last year – although I remember reading great reviews, and being aware of its stature as a work, I think for many years I had unfairly considered it to be a ‘woman’s novel’. Maybe it's a cover design thing – those pastel colours and the little bouquet of daisies on the front.

I think I also picked it up out of some curiosity – the Shields family were well-loved neighbours of my wife Andrea and her family back in Ottawa in the late 70s and through the 80s, and I must have perhaps thought the book would give me some insight into that world.

But in fact the book delivered an enormous amount more. Essentially it’s a family saga of four generations, told through the life of the central character Daisy Goodwill. It’s a complicated story which I won’t elaborate on too much – her mother dies in childbirth and she is raised by a neighbour, and eventually marries the neighbour’s son. And the book's father figures – her own, her adopted father, her husband – die young, or walk away from their marriages, into thin air. Children accumulate and the story fans out into their lives and then returns to Daisy as she grows old, the central pillar of the story. A story of one woman’s life, told in a fairly straight line – first chapter is called Birth, the last is called Death.

And it’s astonishing – this seemingly ordinary life, this woman who considers herself to be nothing special. Shields gets right under the skin of these everyday lives and reveals the teeming multitude of every human life. The details, the emotions, the unspoken words, the night thoughts, the little mysteries that pass between family members. I found myself completely caught up – Shields (who died in 2003) has a stunning and uncanny way of maintaining a double focus: as Daisy declines in her last days in hospital, Shields manages with great skill to keep the reader inside the minds of both the central character and those who visit her, unfolding the awkward conversations that float around hospital rooms.

All of this struck me hard when I thought of my own mother’s decline, and the long empty days she spent in hospital wards, sleeping and waking and passing the time. As I read of Daisy’s reveries and thoughts, I wondered what thoughts my mother must have gone through, the childhood memories and regrets and joys, as she floated in and out of sleep in the boredom between visiting hours.

‘Her body’s planet with its atoms and molecules and lumps of matter is blooming all of a sudden with headlines, nightmares, greeting cards, medicinal bitterness, the odours of her own breath and blood, someone near her door humming a tune she comes close to recognising’.

But the larger message of the book is ultimately the same one that I cling to time and time again – as Dylan puts it: ‘he not busy being born is busy dying’. The idea of feeling and experiencing and living every moment to its fullest, as the clock ticks:

‘The larger loneliness of our lives evolves from our unwillingness to spend ourselves, stir ourselves. We are always damping down our inner weather, permitting ourselves the comfort of postponement, or rehearsals’.

Shelf life: Patti Smith - M Train

Finished the Patti Smith M Train this morning and have felt strange and disconnected since. It’s a book with no story, no real characters apart from Patti herself, and she’s haunted, sleepless, still grief-struck throughout, looking for signs and meanings in everything.

The book is beautifully written, and often seems little more than a series of dream journal entries at times, or diaries of pilgrimages to the graves and houses of other artists – Rimbaud, Plath, Kahlo, Genet - where she leaves little tokens of respect. On several occasions in the book, she walks away from a scene and leaves something behind by mistake – her Polaroid camera, the book she was reading, her notebook.

And the narrative disappears, often for days, in tangents and diversions. She goes looking for a passage in a book and it leads her back to childhood - and then back to her early days of marriage, and back to present day. And all around her, things change – her children are grown and gone, Fred is dead. Her favourite café disappears seemingly overnight like it might have been a dream all along.

At the centre of it all she finds a scruffy old bungalow in Rockaway and prepares to turn it into a shelter from the city, a sun-drenched, sand-blown writing retreat. And in comes Hurricane Sandy and pushes all of that invested hope sideways, almost obliterates it. The bungalow becomes a central theme in the book for me – a reminder that all of our plans are at the mercy of the elements, at the whim of forces bigger than all of us.

I finished the book like someone awaking from a fever, from a dream full of portents and symbols, feeling confused, strangely satisfied and not satisfied at the same time. And in a way, maybe that’s its success as a piece of art. Maybe that’s what she wanted all along – to transfer her own restlessness and flu-like confusion to the reader.

‘We want things we cannot have. We seek to reclaim a certain moment, sound, sensation. I want to hear my mother’s voice. I want to see my children as children. Hands small, feet swift. Everything changes. Boy grown, father dead, daughter taller than me, weeping from a bad dream. Please stay forever, I say to the things I know. Don’t go. Don’t grow.’

A real lady... Remembering Mum - a year on, sharing some images

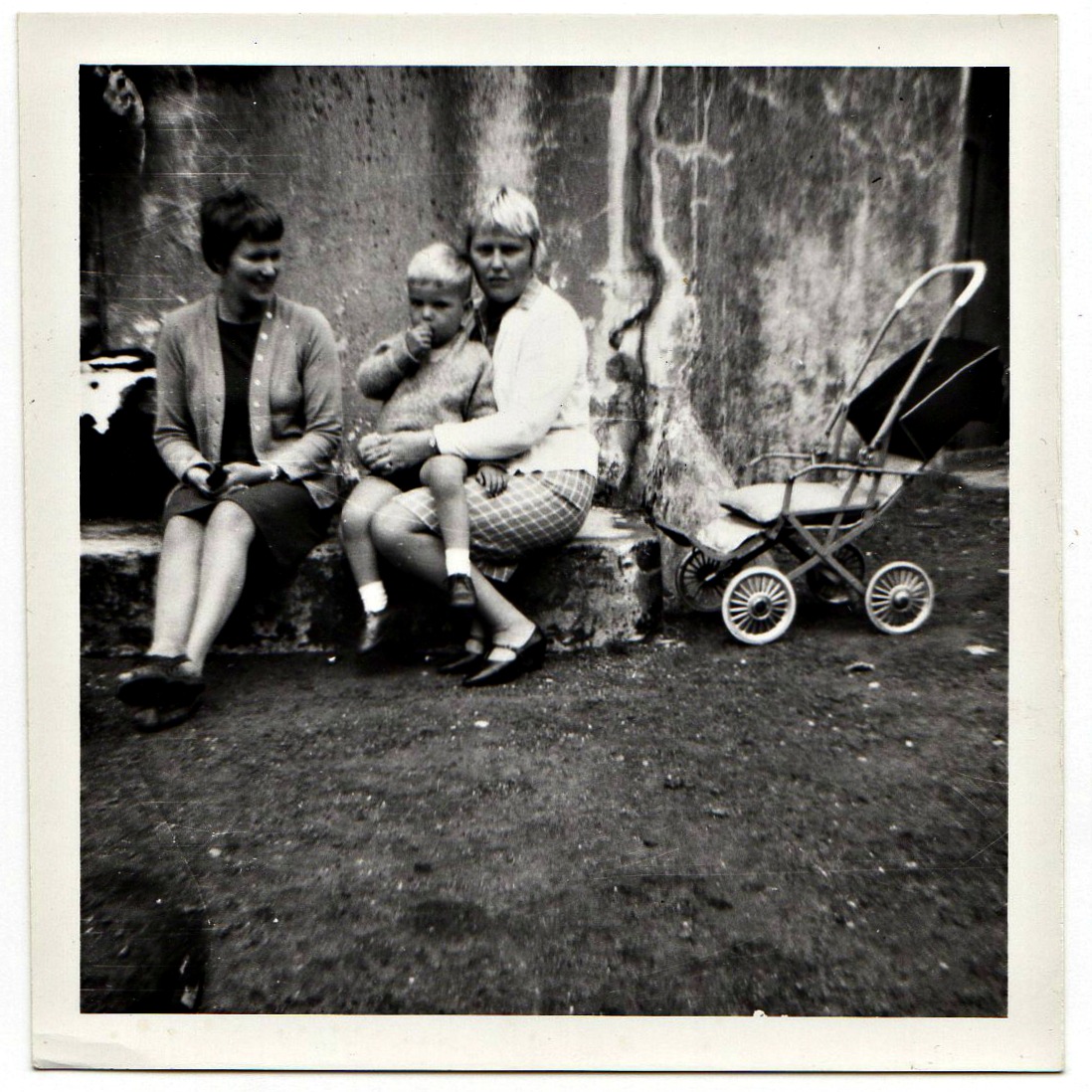

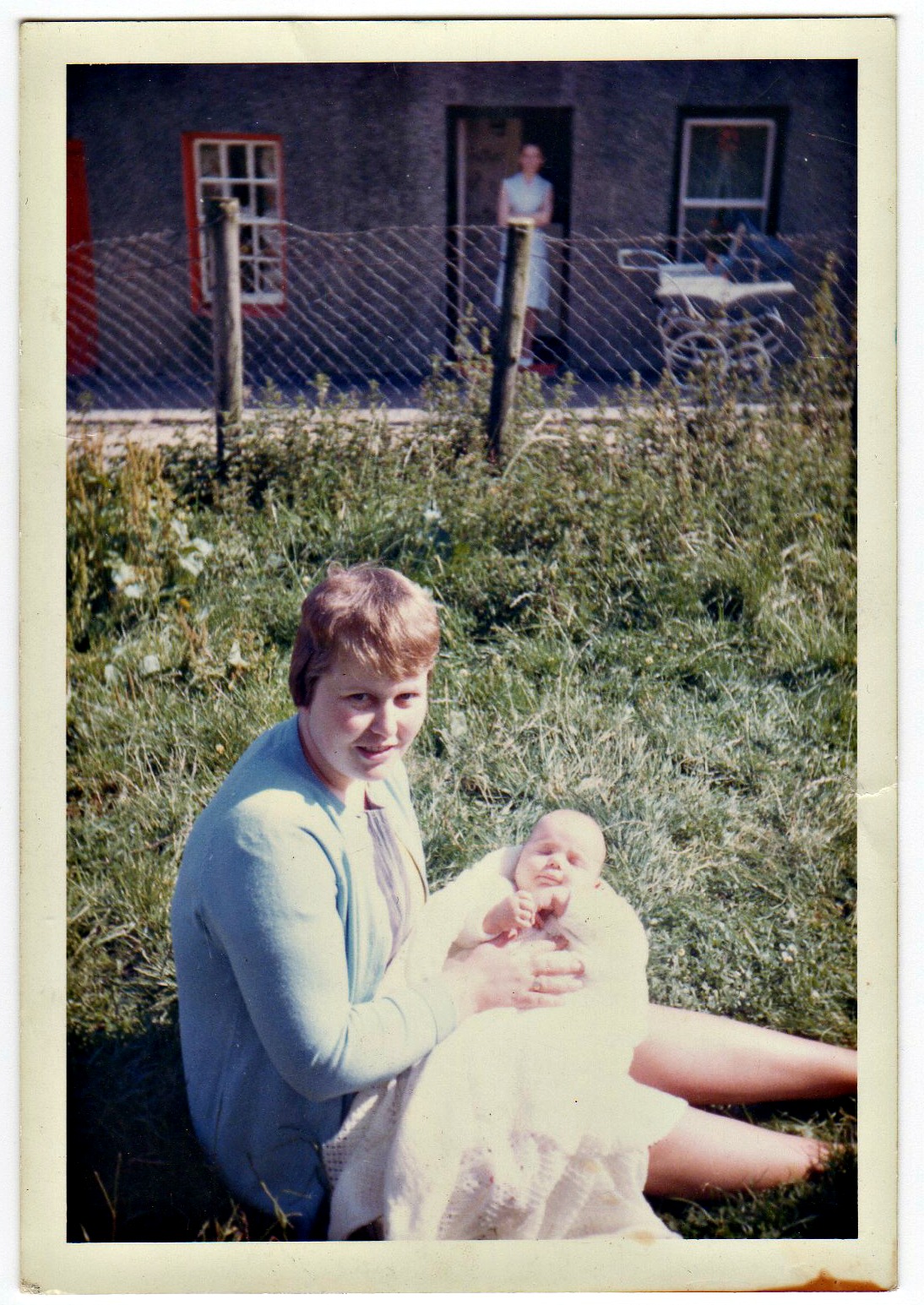

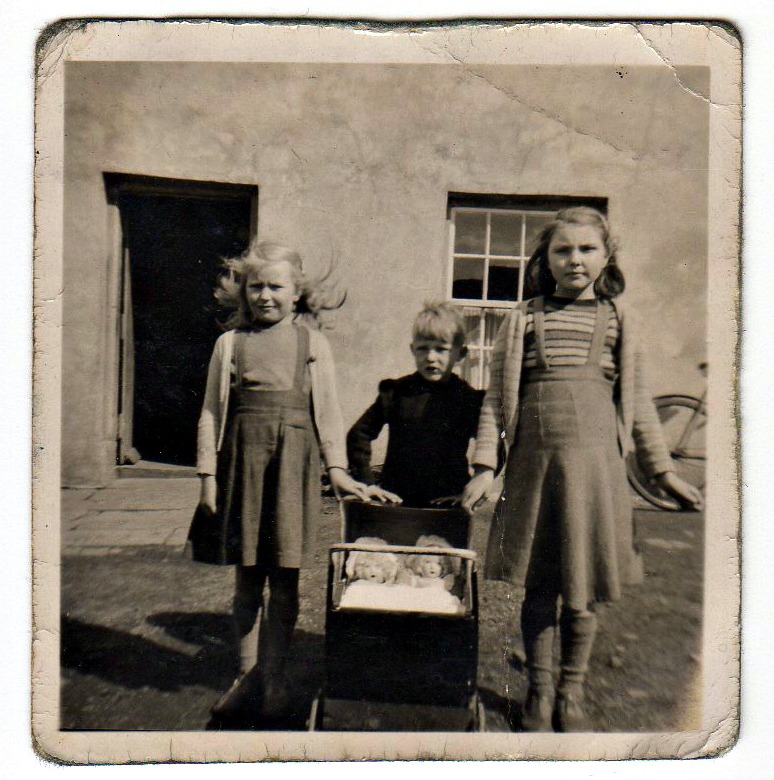

It's been a year since we lost my mother, Eileen Toner - and I thought it would be nice to share this slideshow of images, including all kinds of shots... my mother with me at three months old, with her brother Joe, with Dad on their 40th anniversary, and a number of others throughout her life. Going through her papers, I'm still finding remarkable images every time.

She was a remarkable woman who went through decades of health problems and still managed to smile and radiate charm. I remember sitting across the corridor from her one afternoon as she lay on a trolley at Causeway Hospital and waited for an X-Ray appointment. Two ladies that she knew came along the corridor and saw her on the trolley, and they stopped to speak to her for a moment. Then they wished her all the best and moved on. My mother couldn't hear them by the time they passed me and they didn't know who I was, but I heard one of them whisper to the other: 'That's one real lady there...'

I recall feeling incredibly proud of that - and I couldn't resist telling her about it later, and it really made her smile, at the end of yet another difficult day. A real lady.

Cloudburst in the midlands

Driving east through the Irish Midlands, the crows tossed in a battleship grey sky, like charred scraps from a bonfire, the windscreen pebbled with rain, there's a big Wicker Man-ish statue on the tall embankment to the side of the road, arms raised like some pagan god, calling up the storm. The sky comes down and the world retreats behind a whitish mist, taillights suddenly coming on as the traffic slows in the thundering rain.

(And everywhere, abandoned kitchen and bathroom showrooms, a reminder that not so long ago this whole country was in modernisation mode, all these beat-up, damp old cottages getting the Celtic Tiger makeover. The Sunday Independent has a front page headline: ‘A New Dawn’, suggesting that national happiness or confidence is at an all-time high. The country has repaid its bailout and is on the up again)

I drive through the other side on the approach to Tullamore, rolling into the dry outskirts all at once, like a roller blind being suddenly raised.

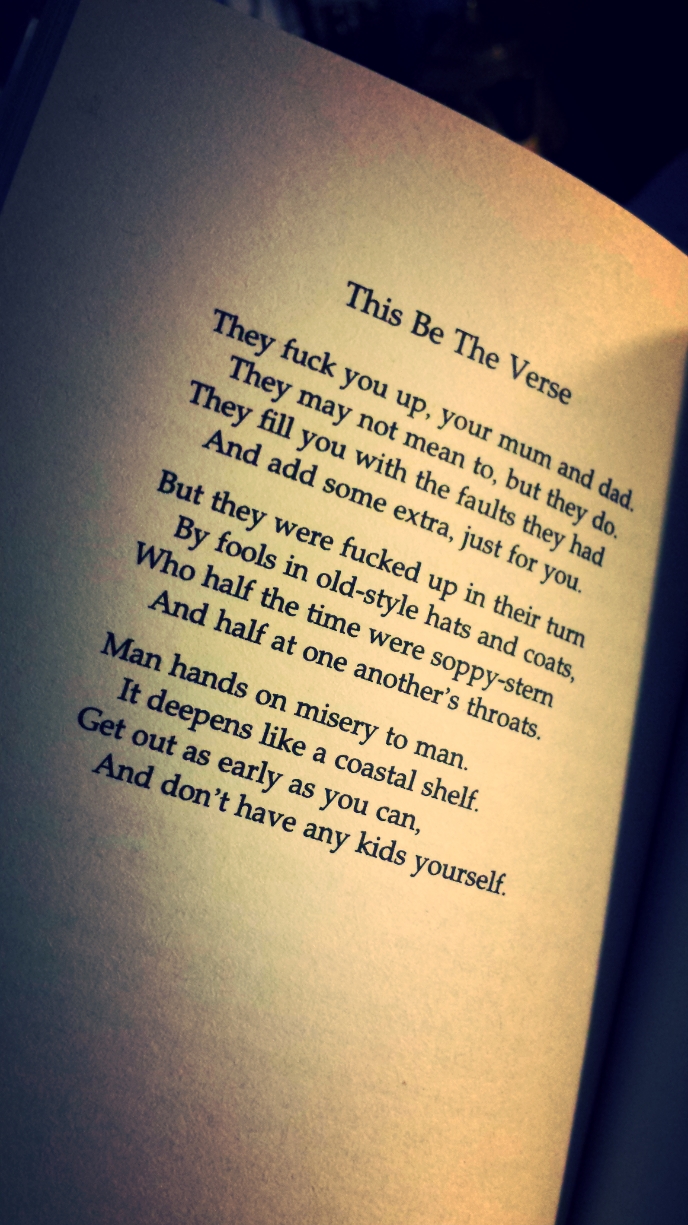

The deepening coastal shelf of... parenthood

The ghost of Philip Larkin followed me home from Sainsbury's the other day.

Over by the cheese counter in the grey empty middle of a Sunday afternoon, I passed a woman struggling with her two boys. The oldest one had plonked himself down in the pram in place of his tired younger brother – and she was trying to encourage him to his feet, while coaxing the younger one back into the pram.

Eventually the older one got up, but by now the younger one wouldn't sit down. The possibility arose that the pair of them might suddenly run off and roam the aisles in a circuitous, destructive escape bid - while she pushed an empty pram for hours down the canyons between the shelves, calling their names in vain.

- Will you sit down? She asked – and he complained and refused.

- Please sit down, she implored him.

And still he refused. I saw her shoulders slump.

- If I give you money, will you sit down?

And she began to rummage in her purse for change.

I got through the checkout and headed for the exit. Ahead of me, an enormous woman was pushing a trolley, packed mountainously high with groceries. This was a large woman in her early 30s – with a stern, long-suffering look, about six feet tall, rolls of fat and muscle across her shoulders and torso. Ahead of her, her husband pushed a similar trolley, also packed to the bows with teetering, loose bags of shopping.

He was also large – a big, shapeless guy with swinging limbs and a kind of beaten, defeated look. In front of him, in the little folding seat of the trolley, his little boy was leaning over backwards, attempting to grab tasty items out of the shopping bags. His father, muttering under his breath, was snatching the bags and jars from his grasp, and putting them back into the bags with one hand, and trying to keep the trolley moving with the other.

Between him and his wife, their little girl sat down heavily on one of the chairs near the café.

- Move, you, said the mother to the daughter.

The little girl, tired and with a slightly mischievous look, stayed where she was and thought about disobedience.

- MOVE!! Roared her mother suddenly, the Sunday afternoon shoppers glancing over as they loaded their own trolleys.

- MOVE… Or be DRAGGED.

And up she got, maybe six years old, and headed for the exit between the trolleys, and back to the family home, to fill the cupboards and the freezer and the fridge, until the same time next week.

Snap by snap - a bridge that leads back to home

My cousin Siobhan and her husband Robert recently scanned, snap by snap, a treasure chest of old photographs that had belonged to my mother and father, and recently they gave me a memory stick with literally hundreds of images on it. Many of them were their own, but there were dozens of mum and dad's shots on there. I'm hugely grateful to them for this - it must have taken days to get through them all.

It has been a joy to go through them - like Christmas morning when you got that big fat annual, packed with comic strips - and you couldn't put it down.

(The pictures above are - my mother and I outside the back door of our first real 'house' at 6 Hawthorn Place, Harpur's Hill, Coleraine; My mother and father and I with my paternal grandmother Mary Toner, at Churchill Park, Coleraine; my mother's family, with her parents Robert and Margaret (I think my mum is on the far right) near their home on the Murder Hole Road between Coleraine and Limavady; and my mother, I think outside her first job, at a bakery on Railway Road in Coleraine, late 50s early 60s)

What is revealed, actually, is the messy, big-hearted sprawl that a family can make over the years - they spread themselves out over the years and the seasons and the townlands and the occasions. There are pictures here from the 30s, right up through four, maybe even five generations. And there are mystery faces among the black and whites, some amazing fashions and just... smiles for miles. My mother and family both came from big families (11 on each side), and when they got together to celebrate, these people took up a LOT of room.

My parents took photographs at almost every occasion - and our house always had a drawer full of those big-bellied Belmont Photographic envelopes, packed with amateur snaps of the weddings of my million cousins. When you scrolled through the pictures, they would always start off with people looking fantastic, wonderfully dressed and groomed outside churches, and always end in pictures of chaos - bottles, cans, cigarettes, ties at half mast, eyes glazed. They had an enormous talent for having a good time, my folks.

Now that my mother is gone, and my father is increasingly out of reach, these pictures are a bridge back for me. And not a tearful journey, either - I have a sense of joy and love looking back at these snaps. I mostly remember having a good time - we loved each other and we ALL had a pretty good time, actually, and I think the pictures tell that story.

Next gig - in the round with Matt McGinn and Ken Haddock, Banbridge, Sat Oct 17

Next Saturday, Saturday October 17 at 8pm, Anthony appears 'In the Round' in the fine company of Matt McGinn and Ken Haddock, in a special one-off concert at Banbridge Town Hall. All the details are included here, in this page from the Arts Programme:

Poor Blue - Mickey stands up in public again

The truth is, sometimes you're just a little too late...

It was so long ago, I could probably fake it, and claim I was right there, at the front corner of the bar near the stage (my feet sticking to the carpet), when the spark of punk set the cobwebs on fire at Spuds in Portstewart.

But the fact is... the Punk thing kind of passed me by, as a live phenomenon anyway. Sure, Rudi and The Outcasts might have played Spuds, but by the time I was just underage enough to blag my way in out of the rain, the circus had already left town.

I was 17, stretched out on the teenage rack of boredom, acne, exams and an enormous melancholy. I took refuge in post-Punk Spuds – The Perfect Crime. International Rescue. The tasty musicianship of bands like Southbound Train, B4, Richmond Hill.

And then I heard The Mighty Shamrocks. And for that year, I caught every gig they played at Spuds. It was the only live music venue I knew. I had virtually no pocket money. But I saved what I could, and once or twice WALKED from Harpur's Hill to Portstewart - and hitched home again in the dark - to hear this band.

Why?

The Mighty Shamrocks - pic by Keith Gilmore

It's hard to define in retrospect. I remember shapes they threw - chins jutting, leather jackets, tinted glasses. Skinny ties. A Roland Jazz Chorus amp. A worn-out Telecaster.

The guitar player sounded like The Pretenders. The rhythm section sounded like Some Girls-era Stones. The singer sounded like Bob Geldof fighting for the mic with Willie De Ville.

I remember 'Breaking up with Harry' most of all. Like 'Reelin in the Years' being sneered by Blonde on Blonde Dylan. The charts were full of image-conscious New Romantics, preening and pouting. And here, in this seaside pub lounge, was this scruffy quartet singing oblique songs about Mexican fishermen and referencing Coronation Street and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. I was hooked – these were actual SONGS. Pop had become so rarefied and refined almost out of its own existence by then – we were in a high-altitude world, all mirrors and image and attitude, and the oxygen was pretty scarce. The song structures had thinned out, too - become little more than skeletons. Coat hangers. Skittery little drum patterns and nervy, processed vocals and guitars.

The Shamrocks seemed three dimensional in comparison. I bought the single - 'Condor Woman & 'Stand Up in Public', and waited for the LP. The band went into Homestead Studios with Mudd Wallace and recorded and album for Good Vibrations. But-

The one and only single... Condor Woman.

The truth is, sometimes you're just a little too late...

The taxman came after the label, the project got shelved and the band went their separate ways - bassist Roe Butcher and guitarist Dougie Gough to other musical projects; frontman Mickey Stephens to academia in the United States and Paddy McNichol (until his untimely death) as manager of the fabled venue Connolly's of Leap down in Cork).

Thanks to fellow Shamrocks fan Fran McCloskey, who had a digital copy, the album, now called 'Paddy', was finally released a couple of years ago. There were a couple of celebration gigs, with Paddy's son on the drums, sparks that could have started fires, and the players separated again.

Now here comes Mickey Stephens again, sounding like he's never been gone, with a new project, Poor Blue, and an album You're Welcome. It's not the Shamrocks - and of course, it shouldn't be - what would be the point? But every now and then when he opens his throat and I hear that yelp, I'm transported.

The swagger remains - he was always a writer blessed with a beautiful reading list and enormous confidence, and on character studies like 'Worth Your Time', he really goes for broke. Top of my list is 'Good for You Daddy', a wonderful lowlife portrait that relies on acoustic guitar and Mickey's delivery.

And the rest of it is laced with brawny Telecaster bite, big drums, Stonesy riffs and memorable turns of phrase. Check out their Facebook page to catch videos and recordings from the band. Copies of the album are available from Head Records and Sick Records in Belfast - and I'm told that copies of 'Paddy' will be available there soon, too, all these years later, You can also download the album from Amazon and you can buy copies by clicking on the CDBaby link here: http://www.cdbaby.com/Artist/PoorBlue.

Epilogue:

Rewind - back to shortly after where we came in. It's early 1985. I'm a teenage dad, out of work and living on an edge-of-town housing estate, miles from the housing estate I grew up in. I've become distanced from my family and friends. Word from home tells me that Spuds is closing. The Shamrocks are gone, the punks have gone. All the people I went to school with seem to have gone. The bands I wanted to form have all fallen to ruins. On some February nights, when the bedtime stories are finished and my little girl has gone to sleep, I find myself slipping into the spare room, picking up the acoustic guitar and quietly starting to work on some song ideas. For the first six months, every one of them sounds like 'Breaking up with Harry'.

The truth is, sometimes you're just a little too late.

Rock Goes to College, 1983 - The Mighty Shamrocks perform Breaking Up With Harry and Condor Woman.

Goat's Milk - a cause for celebration

When I was 12 or 13 (and still kind of friendless) at Coleraine Inst, I would spend most lunchtimes indoors, wandering the shelves of the big library at the school. Like everything else in my first couple of years at that school, the room seemed enormous and complicated to me, with a balcony, and imposing portraits of former headmasters glowering down on damp teenagers hiding from the rain, reading the Daily Mirror.

I didn’t want conversation – I hadn’t found my tongue yet (that would come later). So I had little to say about football or The Clash, and would avoid everyone by hiding out in the baked-dust gloom under the balcony, near the radiator, in the one section nobody else wanted to browse – poetry.

I’d read RL Stevenson’s Child’s Garden of Verse as a youngster, and craved those rhythms, I suppose. Something soothing and comprehensible and bite-sized. Something I could understand and make my own, in a world that seemed about to overwhelm me with its strange rules and unknowable historical significance. And something you could slip into conversation. A name you could drop that would separate you out from the rest of your world. So I would randomly grab slim volumes of poetry from the school library and take them home, and scratch my head in bafflement at the work of poets like WS Merwin and John Berryman.

By the time I left school and found myself in the big bad world beyond, poetry was something I felt I had to leave behind – a luxury that would have to wait, somehow. But in the late 80s, in some second hand bookshop somewhere, I chanced upon a gorgeous thing: a used copy of A Northern Spring by Frank Ormsby. It had a delicious print of a warplane flying over a rural landscape on the front in blue, and simple lettering. It looked inviting and serious and calm all at the same time, somehow.

The central title ‘suite’ is a series of poems spoken by the dead GIs who landed in Normandy on D-Day, in remembrance of their time spent in Fermanagh, preparing for the invasion. I was completely hooked on the idea that each poem came from a different soul, told a different story, but that all of the stories added up to a larger, enormously sad narrative. It was one of those books you read that you never quite recover from.

When I first started writing songs a few years later, I was conscious that I could inhabit other souls, like Ormsby had done. I loved the idea of putting my arms into the sleeves of someone else’s coat and telling their story. It became – and remains - a big influence on me, and I recommend it constantly to other songwriters, as a personal touchstone.

Over the years, I have returned time and time again to A Northern Spring, and I’ve read Ormsby in a number of anthologies – his recent collection, Fireflies, is also a classic.

Anthony Toner meets Frank Ormsby - at No Alibis

On Friday past, as I arrived at No Alibis, I noticed a new Ormsby collection on display – Goat’s Milk: New and Selected Poems, published by Bloodaxe. I immediately told David Torrans I was having a copy of that, and purchased it. And as we were setting up for the concert, I recited a couple of poems and announced that I wanted to read a couple of them during the show, and plug the upcoming launch – at The McMordie Hall in Queens on March 25.

After the soundcheck I went off for a bite to eat, and when I came back, David said: ‘Guess who’s coming to the gig tonight?’ He had called Frank and invited him to the show. And so it was that Frank Ormsby got to be my special guest at No Alibis on Friday evening, reading a couple of poems from the new collection. What a gentleman. What a writer. What an evening – a real high point of my performing life.

Now... If you like what I do, you’ll love what Frank Ormsby does – there’s a direct influence. I urge you to call at No Alibis (on Botanic Avenue in Belfast) and pick up a copy of Goat’s Milk (which has an introduction by Michael Longley, and which contains many of the delightful poems from A Northern Spring - and some glorious new works, too), or even better, come along to the McMordie Hall in the School of Music at Queen’s on Wednesday March 25 at 6.30pm, when No Alibis will host the launch event. I’ll be there, in continuing celebration of this man’s work, which continues to move and delight me.

For more details on the Goat’s Milk launch event, get in touch with No Alibis directly on (028) 9031 9601.

The new album, Miles & Weather - stream the whole album here

Hello, World!

Street suss serenade

Cornmarket, pushing my bike through the post-festive throngs today, everybody in the doldrums, the in-between days of Christmas and the New Year. Suddenly I’m distracted by the sound of somebody singing. That’s not unusual - there are always buskers around that part of the city. In fact, it seems to have become a welcome space for public spectacle – clowns and street entertainers, buskers with Mumford-y beards, little kids with squalling electric guitars, the amazing drummer who plays the empty paint pots, musicians miming to panpipe music, etc.

But this guy was different – he had drawn a crowd. He had set up some kind of MP3 player and an amplifier outside the front doors of British Home Stores, belting out karaoke backing tracks. And he stood out in front of it in a camel coat, with a straw hat on the pavement in front of him, and just... wailed.

I watched him for about ten minutes. Old showtunes, Elvis numbers, 60s hits, he bellowed them all out, throwing his head back, waving his arms and moving around the space he had created. Every now and then a pretty girl would go past and he would gesticulate, offering the performance to her alone. The crowd around him would grow and then retreat, in that unfathomable logic of crowds, where everybody suddenly, wordlessly agrees they’ve stood for too long and they instantly disperse.

But periodically his audience would swell to thirty or forty people, and they would stand in a circle, smiling, just amazed at the energy he gave it. No instrument, no costume. Just his voice. When he didn’t know the words, he approximated them with home-made sounds of his own.

In other words, he was not to be stopped.

I bent over to throw a quid in the hat, and noticed that it was already two thirds full of £1 and 50p coins. Which tells us something, I think – fortune favours the brave. Who dares wins. Something along those lines. I’ve heard a lot of buskers this year – and I’ve made donations to most of them – but this one I’ll remember, because something about his bravado made me smile.

Sliding on Latter Day Sinner

The first time I saw Matt McGinn – who has a lovely new album out that you should buy – was at one of those shows people used to do in the Black Box where a cast of thousands play all the songs from a big album – they had already done Harvest, I think, and Astral Weeks and Fisherman’s Blues, and now it was the turn of The Last Waltz.

Matt McGinn by Joanne Ham Photography

The afternoon (it was a long affair, this) was hosted by the irreplaceable and much-missed Gerry Anderson, who arrived in a fluster having locked the keys inside his Mercedes. Someone from a garage on the Boucher Road had broken into his car and got his keys and charged him £160. ‘I could have left my car in half a dozen places in Belfast,’ he told me, ‘and got that done for nothing.’

Gerry started everything off with a rousing welcome and launched into a spirited version of ‘Who Do You Love?’. I was on early, playing a solo version of ‘Such a Night’ by Dr. John on acoustic guitar. I seem to remember feeling very out place, very subdued among the rackets being generated by people like Jackson Cage and Captain Kennedy and co. But the craic was great.

Anyway, half way through the first set, on came Matt McGinn and tore the place up with a raw version of ‘The Shape I’m In’. I’d heard his name (it’s a great name, blessed with its own rhythm and bounce on the tongue), but it was the first time I’d heard him perform and I thought he was wonderful. Andrea thought he looked like a happy dancing bear.

Over the years, I’ve come to know Matt well, and we’ve done a few gigs and broadcasts together here and there. On his debut album, Livin’, he asked me to play some slide guitar and I showed up at his house badly hungover and attempted to put some licks down over a pretty complicated arrangement. I went home convinced I had let the side down, but when the track came out, he had cut and spliced something wonderful out of it. I tell you, it bore little resemblance to what I offered him that afternoon.

Latter Day Sinner by Matt McGinn

It was good enough though, that he asked me back, and I’m thrilled to have been part of his latest album, the delicious Latter Day Sinner. Once again I’m playing slide guitar, on a song called ‘We’re Fine’, with my playing weaving in and out between harmonica licks from the legendary Mickey Raphael. I think it’s the sweetest song on the collection, but then I would say that. There are some harmonies on ‘Fall into You’ that just make me swoon. And I’m not much of a swooner anymore.

It’s a lovely collection, recorded with warmth and heart and it deserves to be heard by as many of you as possible. Click HERE to order a copy. And click HERE if you’d like to watch a video featuring some selections from the album. And if you’re a downloader and you only want one track, ‘We’re Fine’ is, er... (cough) the one I’d go for...

And if you'd like to see the man perform in person, and pick up a copy of the album from Matt himself, he's appearing at McGrory's in Culdaff on November 13, at the Downshire Arms in Hilltown on November 15, St. George's Church in High Street Belfast on November 19 and Abner Brown's in Dublin on November 26.

I can't guarantee that he will dance like a happy bear at any of those gigs, but maybe if you ask him he might oblige.

For National Poetry Day

'For Tess'

by Raymond Carver

Raymond Carver

Out on the Strait the water is whitecapping

As they say here. It’s rough and I’m glad

I’m not out. Glad I fished all day

on Morse Creek, casting a red Daredevil back

and forth. I didn’t catch anything. No bites

even, not one. But it was okay. It was fine!

I carried your dad’s pocketknife and was followed

for awhile by a dog its owner called Dixie.

At times I felt so happy I had to quit

fishing. Once I lay on the bank with my eyes closed,

listening to the sound the water made,

and to the wind in the tops of the trees. The same wind

that blows out on the Strait, but a different wind, too.

For awhile I even let myself imagine that I had died -

and that was all right, at least for a couple

of minutes, until it really sank in: Dead.

As I was laying there with my eyes closed,

just after I’d imagined what it might be like

if in fact I never got up again, I thought of you.

I opened my eyes then and got right up

and went back to being happy again

I’m grateful to you, you see. I wanted to tell you.

Cheeky face

A journal post from last year: In the coffee shop this morning, a young mother and her friend are complaining to each other about relatives, while her son runs around the café, as kids will do, picking things up and putting them down, his little trainers pounding on the fake wood floor.

I’ve just come from the doctor, whose confirms my suspicion – this cold has gifted me a perforated eardrum, so I’m sensitive to every noise: her barked orders at the child, the steam from the cappuccino maker, even (God bless him) the youngster’s thin, wet little cough, which sounds in my bad ear like a cheap roller skate being thrown down the stairs.

‘Show Tracey your cheeky face,’ she says to her boy, who stands by their table and pulls a face. The women laugh. ‘Show her your cross face… Show her your happy face.’

The little boy grimaces at them repeatedly. They’re all the same face.

To Kill A Mockingbird - revisited

(On Sunday May 11, Andrea and I went with my daughter Sian and her boyfriend Bob to the Queen's Film Theatre to see 'To Kill A Mockingbird' on the big screen)

Oceans of ink have already been spilled on the subject of To Kill a Mockingbird, so there’s really no reason for me to pour my thimbleful over the side of this boat.

But I can’t help myself. What is it about this film that peels me open every time?

Atticus Finch and the children are confronted by the lynch mob

Certainly the central performance by Gregory Peck is a towering example of dignity, courage, integrity and strong, loving parenting. I have to say that Atticus Finch is the yardstick I set myself some time ago as a father.

(I know. It’s an impossible standard to measure up to, but you have to aim for something. There are a number of things that will bring me out in a cold sweat in the small hours of the night. And the thought that I might have been a bad parent is one of them. So I look to Atticus as one of the role models)

The sense of lost childhood is also stronger every time I see the movie – the narration, the idea that this whole thing is already a memory. That’s highlighted, I think, by the soundtrack, which hints at nursery rhyme structures now and then.

Also the look of the film – the overhanging trees, the creaking verandahs, the fallen leaves, the warm darkness... It’s a childhood world seen in memory. It has an unreal quality, like the whole street – the trees and yards and houses – was created in a vast film studio lot - indoors - and lit to look like reality, but feels instead like something you dreamed.

It’s an archetypal southern landscape too, all those heatstruck ladies and the kindly black maids, front porches and screen doors, chirping crickets and tree houses. People sitting outdoors at night on a porch swing, fanning themselves in courthouses, the rattling cars, the pocket watches and waistcoats.

It has been many years since I saw the film, and Sunday past was my first time to see it on a big screen. It has lost none of its power to move me. Almost from the minute they put Tom Robinson on the stand through to the last line... ‘he would be there all night, and he would be there when Jem waked up in the morning’ - I’m in tatters.

What do I weep for? The first novels that really made an impression on my teenage mind were Southern Gothic classics - Harper Lee's Mockingbird, Truman Capote's A Grass Harp, Carson McCullers' Ballad of the Sad Cafe, and as a result, it's a world that makes me nostalgic when I go back there to visit, like a sentimental tourist in my own childhood.

What do so many of us weep for, anyway? Our own lost childhoods, I suppose. In my case, lost opportunities to be a better father, too, I’d guess. As always, the sense that time is slipping through our fingers and important things are being missed.

Linley Hamilton - picture by Ken Haddock

Sharp as ever - Linley Hamilton's 'In Transition' is out

For many years, as someone who worked in a music venue by day, and played gigs in the evenings, I have considered Linley Hamilton to be someone who played with the same impeccable taste - and with the same attention to detail - as he dressed.

He always seemed to play with cool people, and he breezed in and out of venues looking sharp. There are few more instruments as cool as the trumpet to start with anyway, right? And a sharp dressed trumpet player is exponentially more sharp than any other sharp-dressed musician.

And Linley seemed capable of playing ANYTHING. With ANYBODY. He has turned up in the most unlikely combinations - and always delivered something appropriate, unexpected and delightful.

The first time I saw him play live was with the Dermot Harland Quintet at the Edgewater Hotel in Portstewart in the early 90s, and as the sun went down on the Atlantic beyond the windows, he played an exquisite solo on ‘When Sonny Gets Blue’, and I was hooked.

He has progressed leaps and bounds even since then, and he remains an arresting talent – he has played beautiful trumpet solos for me on three of my albums, and on each occasion he has been exquisite. It’s a source of huge personal pride for me to share the stage with him occasionally as my guest, or when he augments the Ronnie Greer Blues Band line up.

The reason for my gush is that Linley has released a delicious second album called ‘In Transition’. It's a beautiful thing, and features performances by Linley backed by a superb band - Johnny Taylor on piano, Damian Evans on bass, Dominic Mullan on drums and Julien Colarossi on guitar. Highlights include a beautiful arrangement of Rufus Wainwright's 'Dinner at 8' and Linley's own composition 'Dusk'. You can find links to the album here:

At Amazon, and at Spotify, and at Lyte records: http://lyterecords.com/

Haunts of ancient peace

Crawfordsburn Country Park, Bank Holiday Monday - picture by Andrea Montgomery

I have always enjoyed forest trails and walks. Some of my fondest childhood scenes are set in the woods.

On blazing summer days at St. Malachy’s Primary School in Coleraine, our headmaster Frank Molloy used to occasionally arrive unannounced in our classrooms and take a couple of dozen of us on a stroll around Mountsandel Forest. He would tell us the names of the trees, talk about the birds and wildlife that lived in the forest, and excite us with fanciful tales of highwaymen riding along the trails to escape capture. For a kid who had caught the bus in from the housing estate that morning, it was an unexpected trip to a leafy world filled with wild noises - with a beautiful high green canopy and a warm, soft floor.

My father and I, Roe Valley Forest Park in the mid-70s. The little pot belly, the steel-framed specs and the binoculars: Just a MAGNET for bullies.

My dad already knew the names of the trees – he had worked for a sawmill as a young man and knew his ash from his chestnut. When I was in my early teens, we got our first car – an Austin 1200, I seem to remember, in a nostalgic royal blue - and as a family we would often head out for Sunday drives to places like the Roe Valley Forest Park, where I would stare through binoculars, looking for anything other than sparrows and jackdaws.

Today Andrea and I went out for a walk around Crawfordsburn Country Park – and had a beautiful stroll along the stream there, with the banks just misted purple by bluebells. It’s a beautiful space – it was lovely to be in under that bright green roof, and then find ourselves skimming stones on the beach ten minutes later.

Both of us felt the oncoming rush of the spring – things starting to come up out of the ground and make themselves seen, the sky seeming to lift a little higher.

I’ve just had a month or two that have felt like a low-level hibernation of the spirit, so it’s good to feel the ground warming up again, the sense of promise renewed. Bring it on.

Brendan and Declan Murphy - The 4 of Us - live at Flowerfield Arts Centre, March 27, 2014 as part of Ralph McLean's BBC Radio Ulster outside broadcast.

![2014 Eileen [ Dickson ] Toner. R.I.P. 25-11-2014.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/514629e6e4b04055d3084cb8/1448409523957-1VF9L9W1TJWW7OGJ6V5B/2014+Eileen+%5B+Dickson+%5D+Toner.+R.I.P.+25-11-2014.jpg)