'When you think you can't face another day,/ they pick you up and carry you all the way.../ M is for Mothers' - An Alphabet

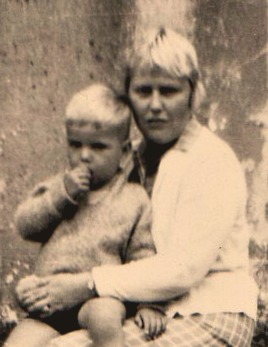

There’s not much I can write about my mother Eileen (1941-2014) that I haven’t already said. Her absence from my life has left a hole that regularly floods with complicated memory and gratitude.

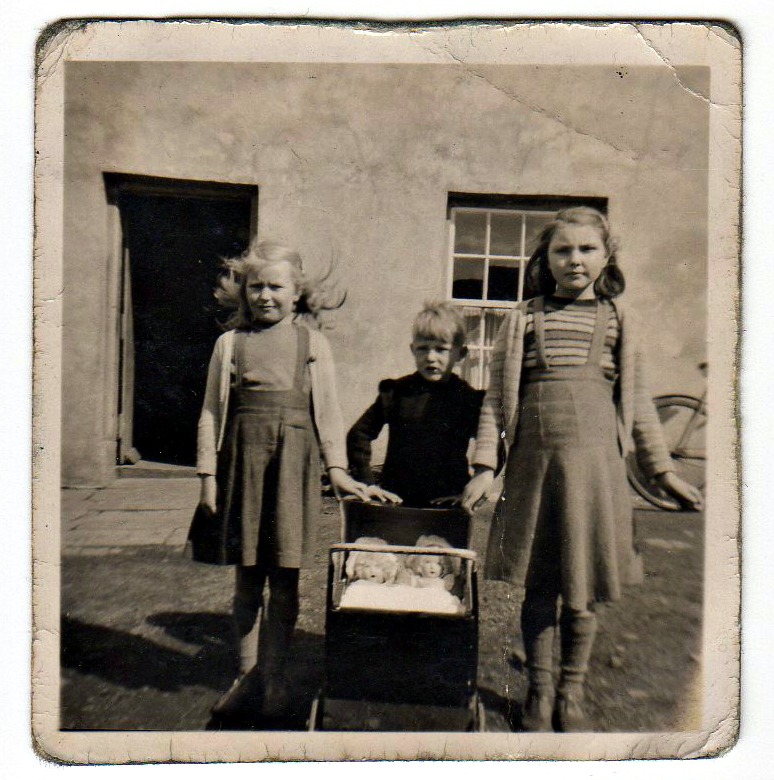

Sarah Eileen Dickson was born on the high ground between Coleraine and Limavady, on the Windyhill Road – or, as it was more colourfully known in my youth, the Murder Hole Road. Her father Robert was a shepherd up there in the hills, living in a cottage at the end of the Bolea Road, tending a flock of sheep for a landowner, and he and his wife Margaret had a flock of eleven children – with my mother the youngest girl.

Her memories of that childhood, as related to me, were basically an Irish version of Little House on the Prairie. Tight, loving family connections, long walks to school in all weathers, milking cows, fetching water, fresh eggs, home baked bread… It was a source of fun in our house that my parents’ backgrounds were so far removed from each other – their only shared characteristics were, essentially, poverty and love.

(my dad grew up a ‘townie’, in Pates Lane in Coleraine, fatherless from the age of eleven. The hardscrabble mid to late 40s. He recalled being sent out at night by his mother with a bag, to cross the bridge to the entrance to Kelly’s coal yard, and gather up any bits of coal that might have fallen from the wagons. He used to tease my mother about being from the country, still having straw behind her ears)

As they grew to maturity and got married, my parents could never quite believe their luck, coming of age in the Never Had It So Good generation - the late 50s and early 60s, when jobs were plentiful, and the future looked bright. And by the time I was a teenager in the 70s, my parents were living in their own house, with central heating, a washing machine and electric cooker, a colour TV and a car.

The pace of change must have been bewildering. A lot of kids born in my time, in their middle ages now, have rolled their eyes at their parents’ mystified response to technology – like their parents are… country bumpkins or something, tutting and marvelling at mobile phones and iPads. But when I think of the DISTANCE that my parents’ generation had come in lifestyle terms - of improvements in living conditions, availability of medicine, home appliances, entertainment, transport, food… it’s really no wonder. It was a standing joke that my mother would be amazed by… pesto. By the existence of something like a mango. Online banking, satellite navigation and mp3s.

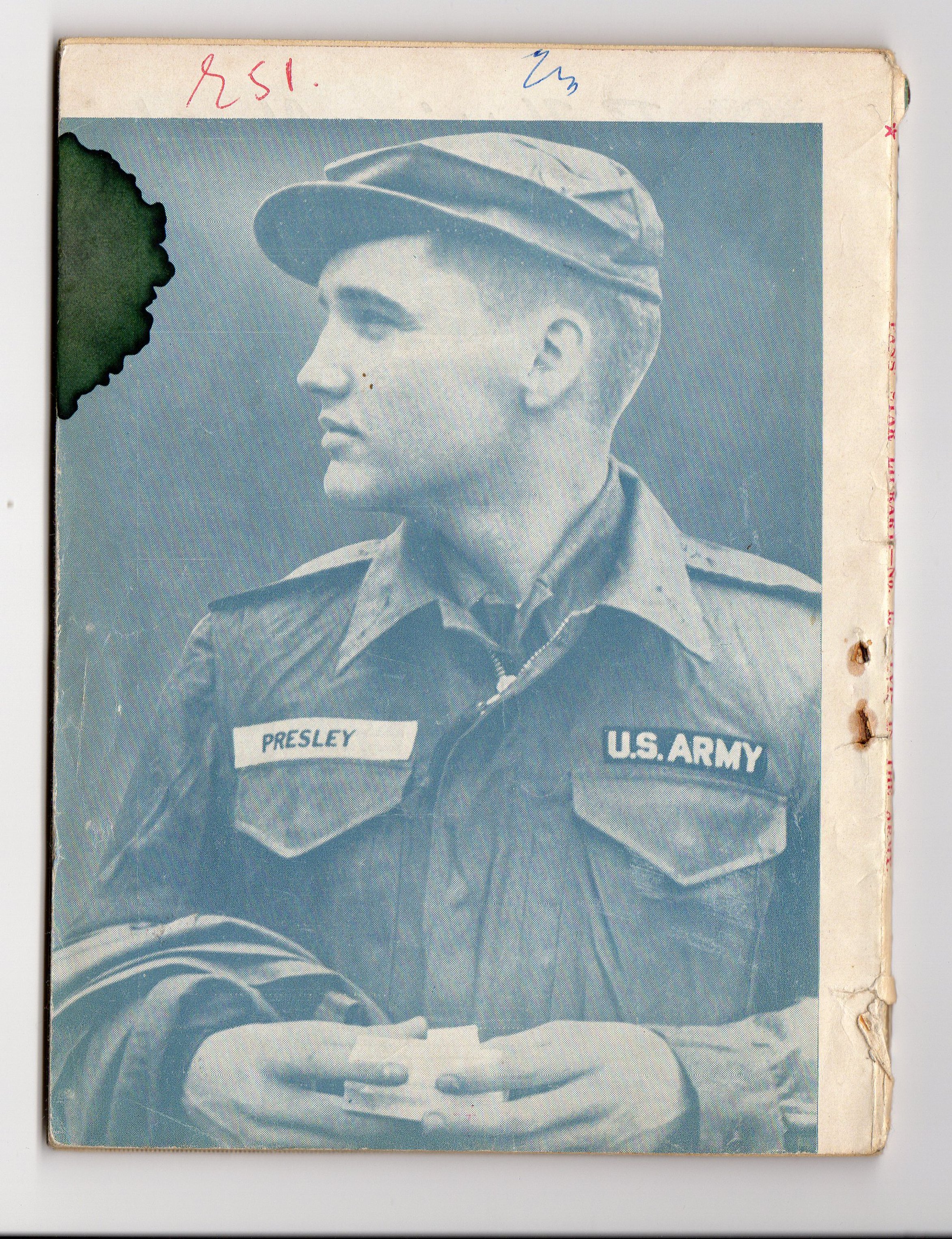

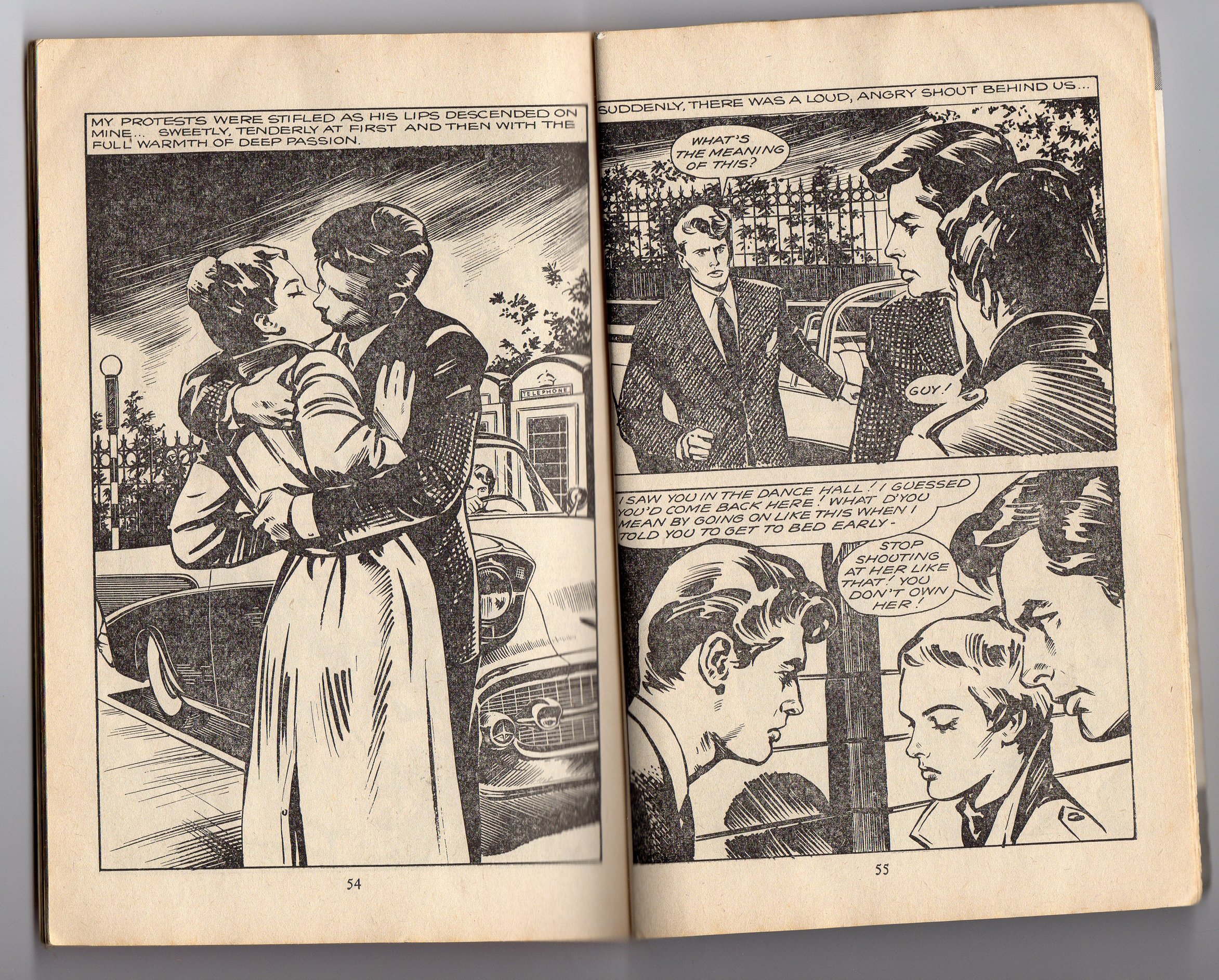

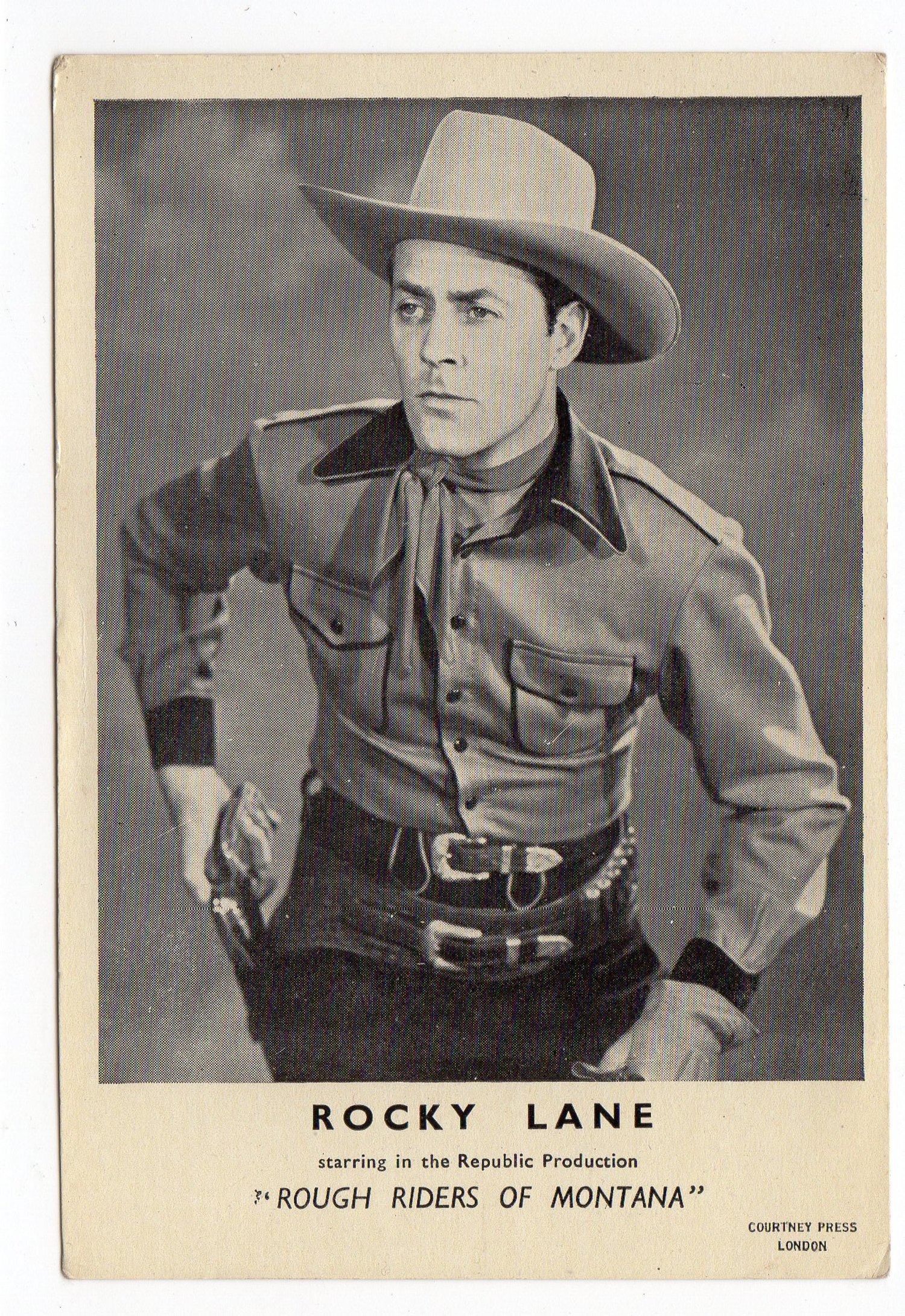

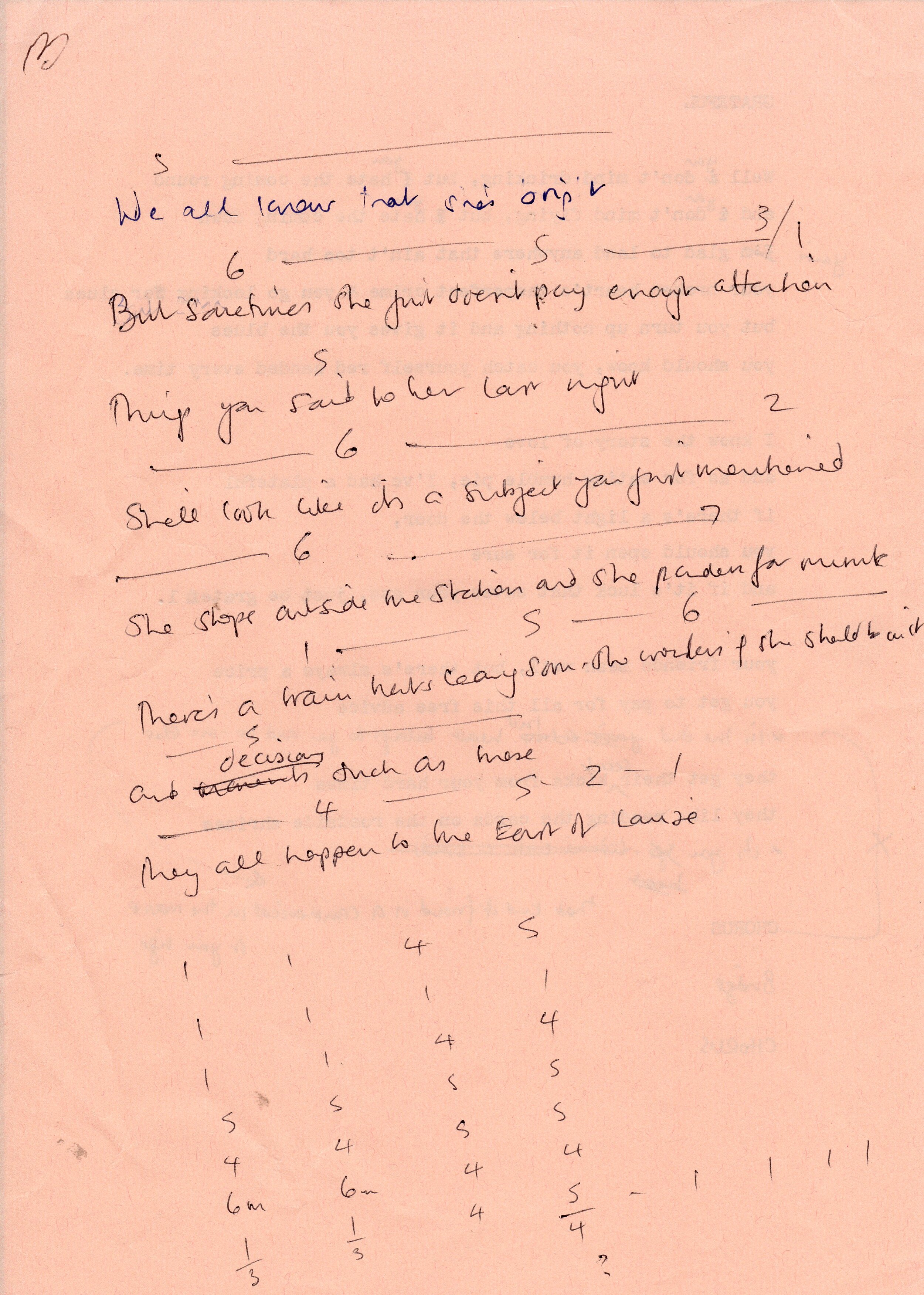

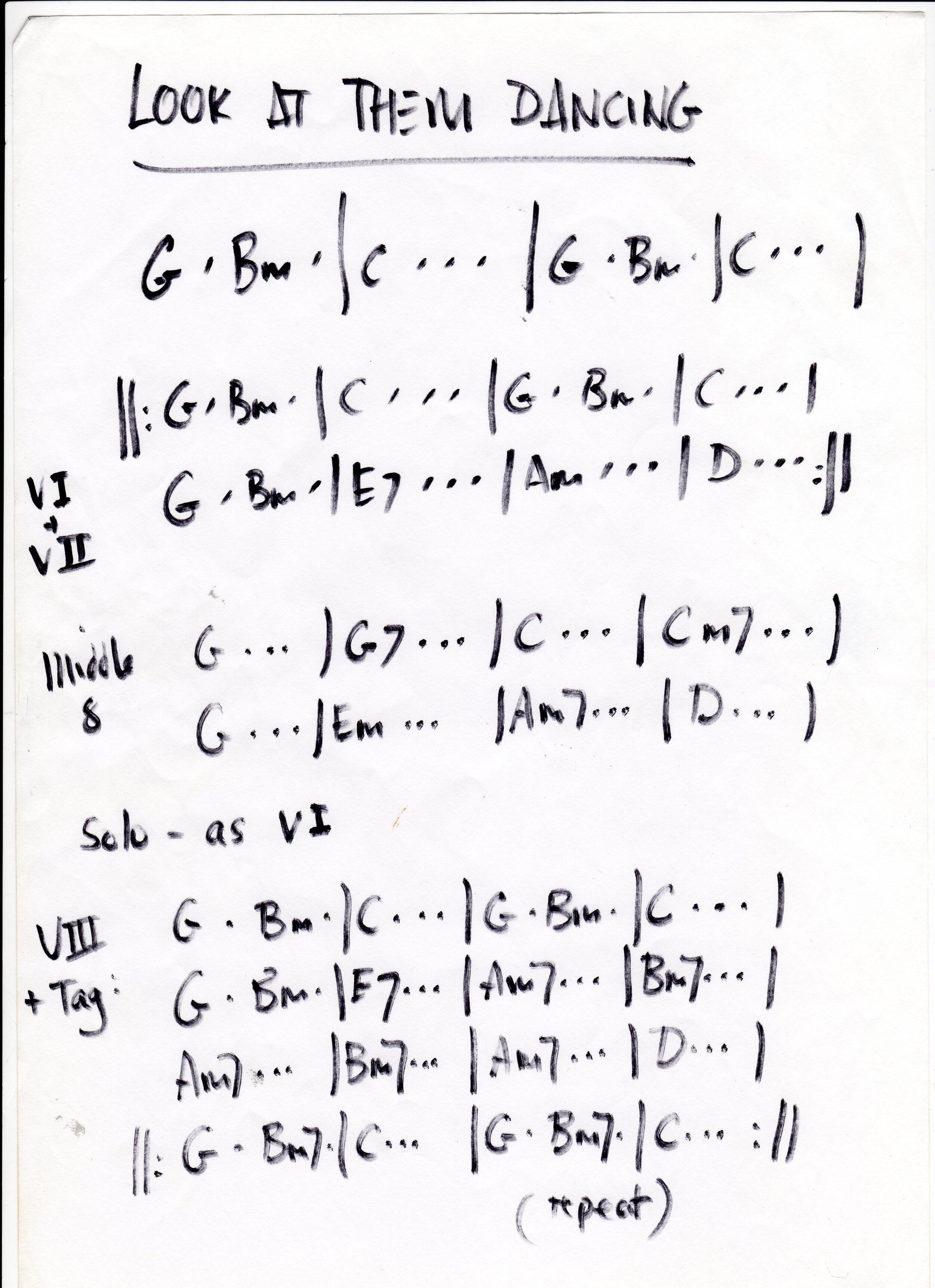

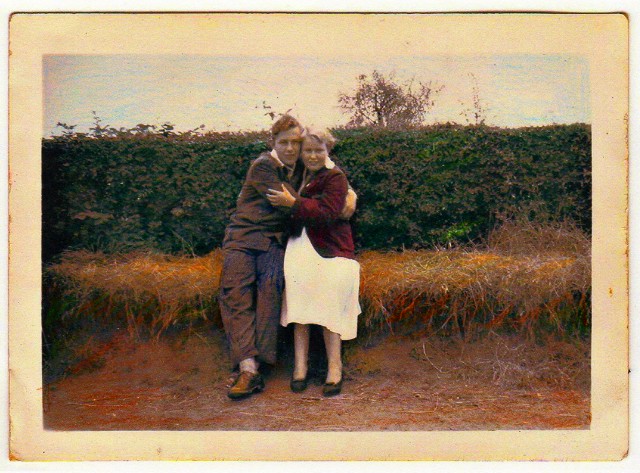

She and my father also shared a well-developed talent for having fun. They met in the late 50s, in the dancehall days, and as a child our house remained full of the old time rock & roll records that they had loved and danced to as kids – Chuck Berry, Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis. Music was a constant thread – neither of them played an instrument or sang that much, but they loved their music. And they were willing to give everything a go. They loved a lot of the stuff I listened as a youngster, especially Dire Straits and Bruce Springsteen and James Taylor. But also, let the record show, Pink Floyd and AC/DC. When I was working at Flowerfield Arts Centre in Portstewart and running concerts there, my folks would come down and sit through just about anything - string quartets, modern jazz and contemporary folk. Often with puzzled expressions. ‘Something a bit different,’ my mother would say to me in the car on the way home, after an evening of screaming saxophone bebop.

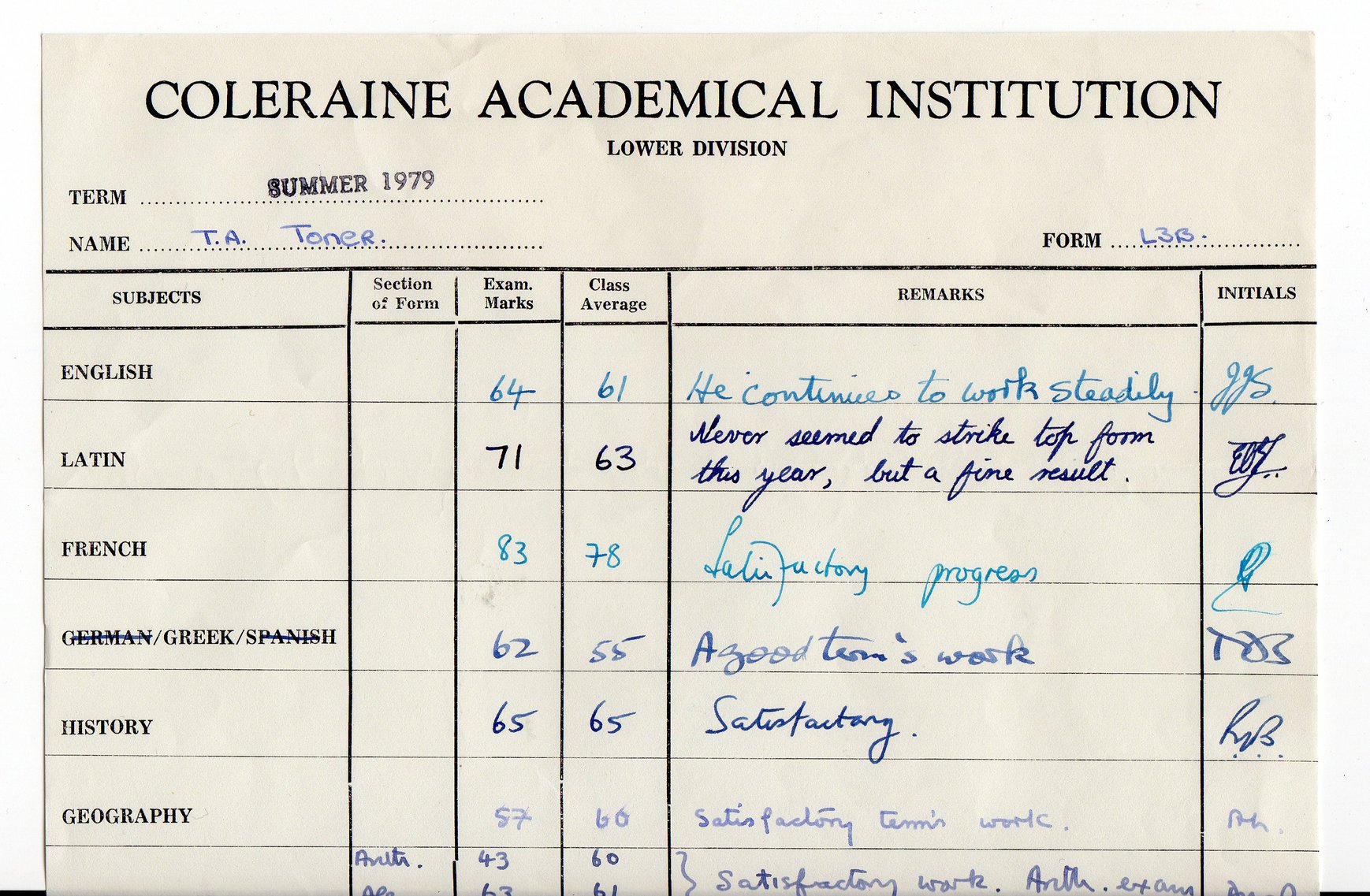

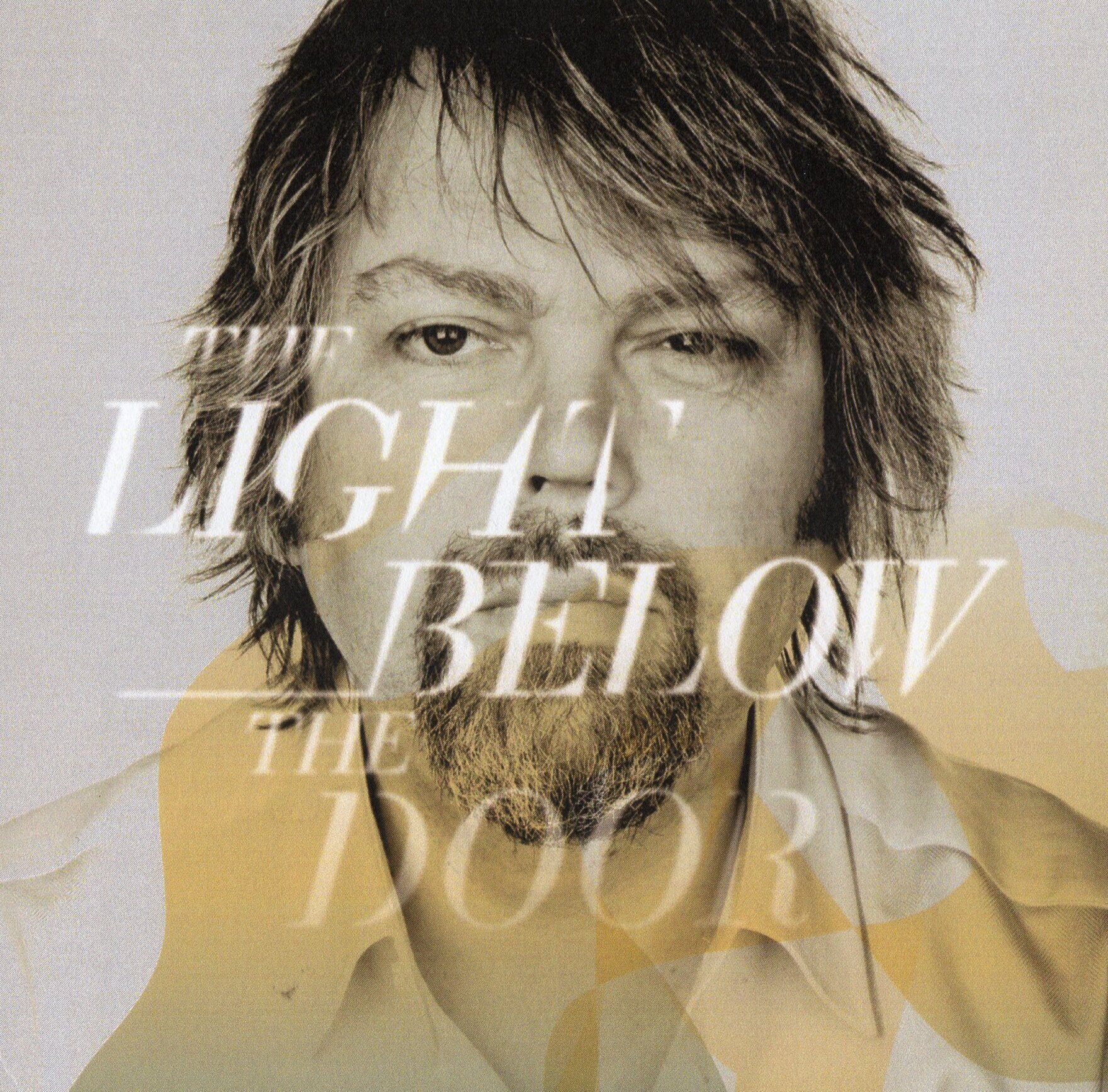

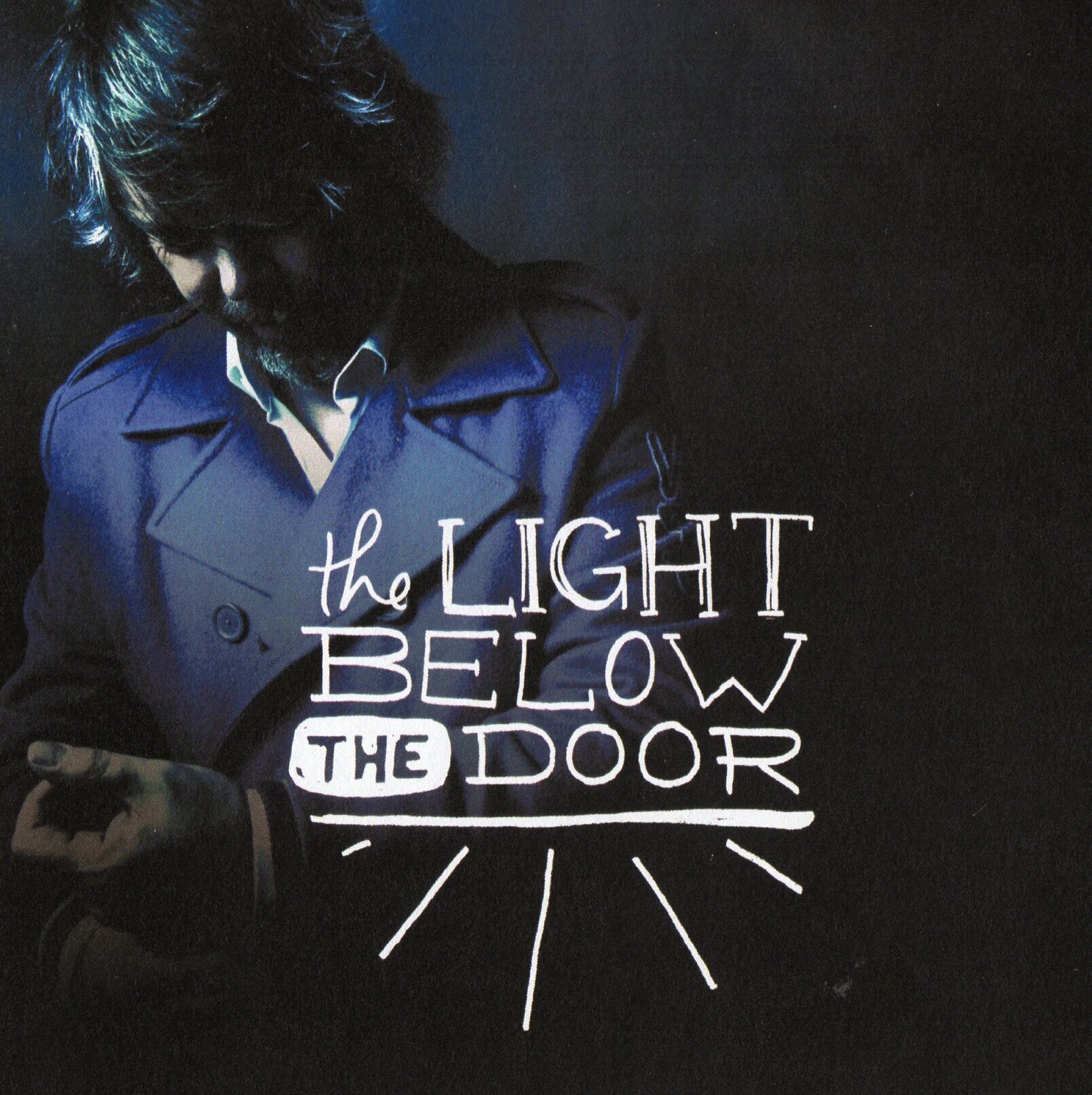

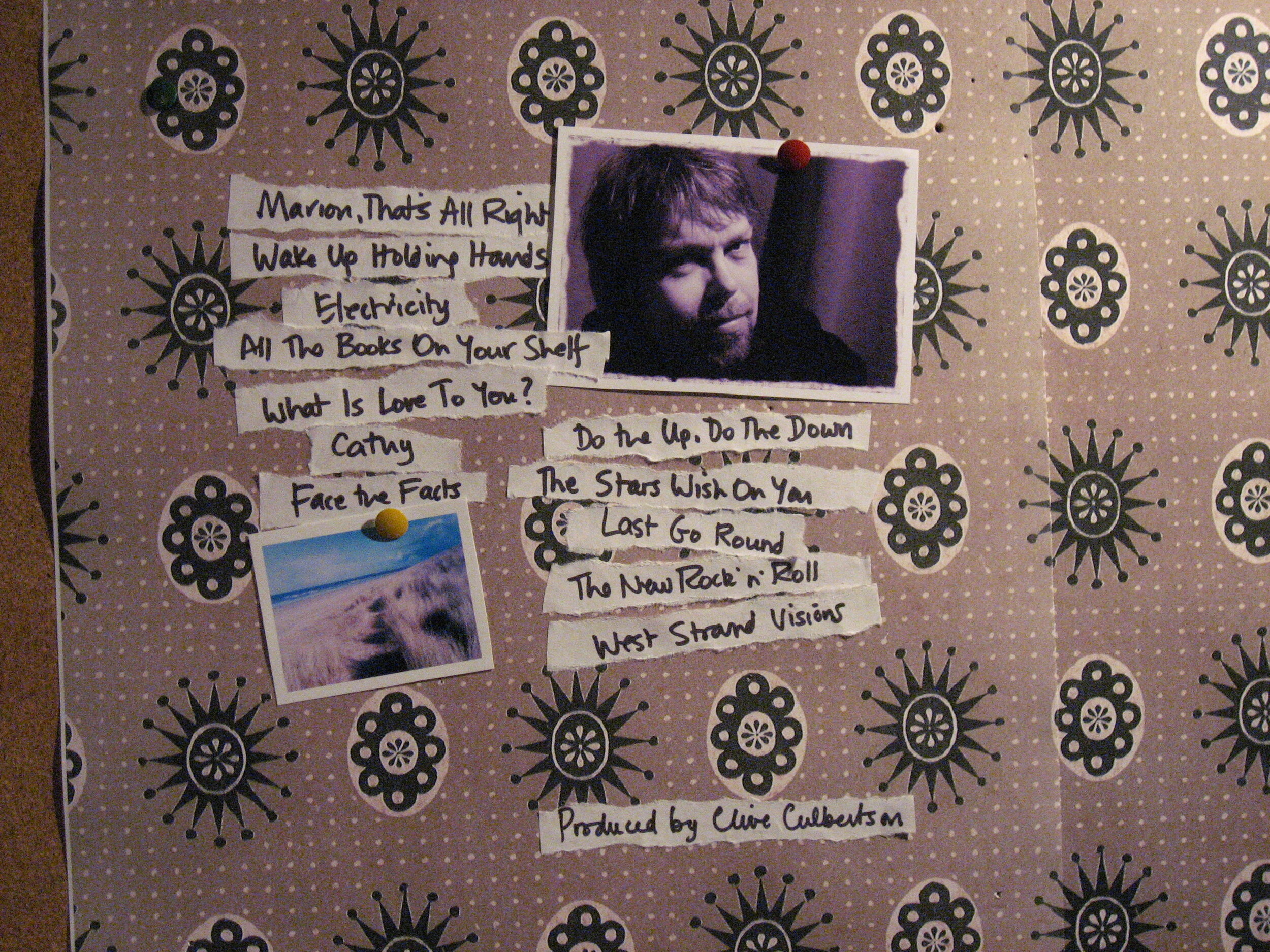

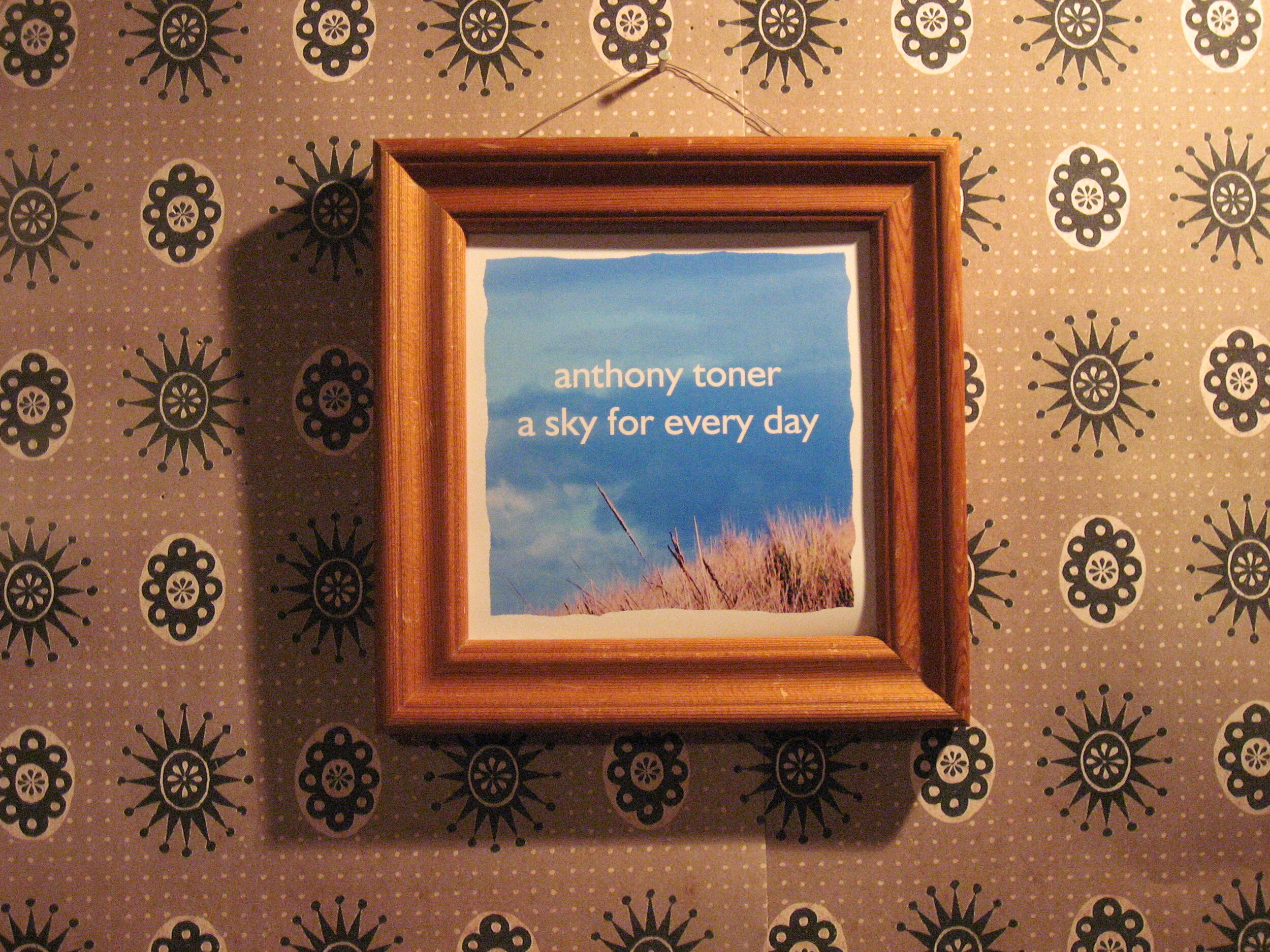

Their lives were intertwined from the moment they got together, and it would remain that way to the end. And I was their little golden boy, of course, through it all. From the moment I could play a D major chord on the guitar, I was the Jimi Hendrix of our street as far as they were concerned. When I was playing in pubs, they would get a taxi there, and I would drive them home in high spirits afterwards, the car filled with an aroma of rum & coke and cigarette smoke. At ‘proper’ concerts later, I would introduce them as the ‘Secretary and Chairman of The Anthony Toner Fan Club’. After my mother died, I found a plastic folder, packed fat as a rugby ball, with clippings about me from the local papers. Every concert, every article, every photograph.

She was pretty strict, though – she’d had a Presbyterian upbringing and a lean childhood. So, I didn’t get away with much. Good manners were expected, and under no circumstances was any success ever allowed to go to my head. And I was overly protected – I was never allowed to climb trees, swim in the deep end, ride my bike beyond the streets where I lived. And that conditioning has been slow to leave – to this day, I’m incredibly cautious in new physical situations.

She remained deeply proud of me and we were in daily contact, sometimes even more often, when her last ailments began to affect her.

When my mother died at the end of 2014, it brought to a close a sad and painful half a decade. She had been a diabetic from the age of seven, so as she entered her late 60s, she had begun to suffer circulation and vascular problems, kidney problems, heart problems. And like so many people her age, one set of health challenges would be affected by another - this medication for that condition would react with that medication for this condition, and thus her body became a battlefield, on which differing ailments and cures warred with each other.